When I was a kid and found out that my dad was an ‘engineer,’ the vision of him driving a train popped into my head because the word engineer was firmly associated with driving a locomotive. It was a few years until that image became disassociated as I learned the reality that engineers do all kinds of things entirely unrelated to trains. But the connection between engineers and trains never completely went away. Today’s Throw Back Thursday explores a train tragedy due to a failure of judgement—and one hero’s ultimate sacrifice.

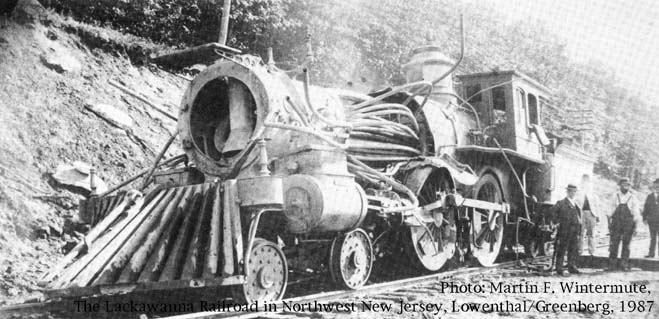

The development of steam-powered locomotives grew rapidly in the early and mid 1800s. By the turn of the twentieth century, these machines, fired by wood, oil or coal, were used to transport goods and people across the globe. Often, the technology, materials, design and construction were pressed beyond their limits. As a result, steam-engine explosions were not rare—and were often violent.

Locomotives were also used for back-woods work in the clearing of mighty forests, where we join two loggers whose fates are cast by the catastrophic failure.

[North of Waterville, ME. Fall, 1899] The day’s duty was to clear slash from the previous weeks’ cutting and make clear the way to begin hand-skidding felled trunks from the edge of a steep incline down to the river. This meant moving the smaller trees and brush and laying them so the logs could be moved to the main road. It was dirty and difficult work. The skidding team used a combination of horses and steam-powered donkey engines to pull the logs out and collect them onto the skid tracks that led down to the water’s edge, where the logs were floated out and to the mill, fifteen miles downstream in Waterville.

The locomotives were loaded by workers known as wood hicks, wielding peavey poles, or cant hooks which were lever tools with a pivoting, hooked arm and metal spike used to gig the log and, using the leverage at the end of the long handle, roll the logs onto the flat bed of the locomotive. The trains themselves weighed 30 tons, driven by split wood fed into the firebox of the train. The most popular type of train were the Shay-geared locomotives that were developed for use in the logging camps. The loads were large and the track hastily constructed, and often uneven and bent. The Shays powered all the wheels of the large engine via a central shaft and gear distribution to the locomotive trucks, greatly increasing the traction of the rig over the rudely built tracks.

The Shays were slow but strong and could pull some of the largest loads up steep grades while not pounding the track to pieces, unlike other locomotives of the time. The machines were hardy, but the harsh conditions in the winter made maintenance difficult and camp bosses, attuned to the costs of idle labor and lost opportunity of blue-sky days, pushed the men and equipment past their physical and mechanical limits.

Steam locomotives were built of thick steel in a bottle-shape with a firebox—lined with firebrick—on one end of the bottle. The plate above the firebox that separated the fire from the boiling water—called the crownsheet—was one-half of an inch thick. The job of the fireman was to maintain the fire to keep the steam pressure available for the cylinders, which, in the Shay, consisted of a triad of push-pull cylinders, the steam sent alternately to the top and bottom of the cylinder, providing motive force at each half-cycle of the piston travel. Maintaining the level of water in the boiler was critical, for if the crownsheet were uncovered, the steam would become super-heated and the crown would fail, with catastrophic results. This most often happened as locomotives crested hills under full power. If the water level was not carefully monitored and was allowed to drop too low, the water would flow away from the crown. Thus, the driver was constantly monitoring the level of water in the boiler through a sight glass in the cabin.

Maurice and Dragos, fellow loggers with an unexpected connection, were walking along the track to the higher reaches of the logging operation. The day was nearly done and this was the last tract to clear before the mid-winter sun disappeared behind the blue mountains.

“Maurice, Maurice!” Dragos cocked his head and looked at his friend who had a vacant, far-off look. “What are you thinking about?”

Maurice, shaken from a temporary reverie, replied, “Uh, yes. It is nothing. I was just wondering” He trailed off, trying to compose himself, and then asked “Dragos, what brought you East?” Maurice didn’t expect the answer.

“I am, or was, looking for someone.” Dragos replied.

“Who?” He said distractedly, trying to focus on his friend, who had something important to say.

“My mother.” He looked at Maurice expectantly. “Her name was Thérèse. Thérèse Ouvrier.”

The train groaned by, moving up the tracks. Maurice said something, but Dragos could not hear it for the noise of the Shay. Steam was spitting from the pistons as the train passed by, pulling uphill to the left of the pair of men. The driver was leaning out the window, watching the progress of the train on the newly-laid track, his left arm on the throttle, goosing the engine slowly up the incline.

“What did you say?” Dragos yelled over the noise. He had heard, but couldn’t quite fathom the possibility.

Maurice looked at his cousin’s face. A great many questions were answered and the next chapter scribbled itself out across the pages of the journal, not in his hand, but in his mind’s eye he saw it.

Suddenly, the train lurched hard to the left and there was a great sound of cracking timber. The driver yelled above the noise of the steam and the sound of the train breaking through the un-shored portion of the track and hit the brakes, simultaneously pulling the reversing linkage hard, grunting. The wheels stopped and then spun quickly backwards, but the momentum of the huge machine was too great, its perch too precipitous. The train continued to pitch forward and to the left, the bulk of the weight of the behemoth over the left wheels of the train truck. The driver pushed the throttle fully forward and the pistons roared, churning furiously, the wheels spinning backwards now at full speed, but to no effect save to chew through the rails, the wheels turning motion to friction to heat and heat turning wood to smoke and flame.

Chunks of wood flew forward of the train as the wheels rotated backwards, a big limb clanged hard into the connecting linkage, bending the rod and pulling the rotation of the steel wheel out-of-round, the left wheels of the train deformed the track and the train lurched hard, once, then again, pitching the driver from the controls, which were set at full throttle, full reverse. He fell against the fireman, who was struggling to shut down the air inlets when the train tipped, knowing that they didn’t have much time before part of the machinery would fail due to heat and the battling mechanical forces.

The engine now screamed above the roar, metal grinding at great speeds making a screeching, hideous howl, rinds of steel peeling off from the thin guards, ripped away and caught in the rotating wheels as the machine tore itself apart. Smoke poured out of the stack, adding to the confused scene: shouting men and failing machinery and wood and smoke and steam mixing with the yells of the men and rending of metal.

Maurice realized his oversight and failure to get the track repaired. He ran to the front of the train, bent down to look and confirmed his suspicion: the supports had splintered and the rail sagged under the weight of the locomotive. He cursed and looked back as Dragos sprinted to the engine as the wheels slowed, steam still belching through the valves. Steam and grease sprayed onto the ladder to the cab, the heat igniting hot oil and fire began creeping up the rungs. The bowels of the engine groaned and three low-pressure steam lines popped free from their fittings, hissing and spitting.

Inside the firebox, fully stoked and now agitated to a greater heat by the motion, the coals flared red and blue; wood and smoke and fire roared. The tender had not been refilled, at Finn’s urging, because the trek to the nearest water would have taken 30 minutes to complete. What was worse, he urged the crew to get underway and started the day off with little more than half the water in the boiler. As the train rolled front and listed to the left, the water ran away from the highest part of the crownsheet, the half-inch thick steel that separated the boiler water from the fire.

The now-dry crown began to soften, stoked to above melting point by the intensity of the fire in the chamber, now a blast furnace. The driver scrambled to his feet and watched in horror as the water dipped below the sight glass. The easiest way out of the doomed locomotive was down, but the exit on the left of the cab was blocked by a large tree that the engine lay into. The wheels spun to a stop as the water, concentrated on the left, cooler side of the boiler, gave off less steam to the pistons. He scrambled up the inclined floor, slipping and grabbed the railing on the door.

He yelled at the fireman. “Get out! We’ve got to get out of here!” The fireman clawed his way forward, holding onto the driver. The driver saw Dragos, now up on the ledge of the engine, furiously working the door latch. “Help me!” cried the driver, who was hanging on the hand rail, holding the door shut against Dragos’ mighty pull. Dragos recognized the two men as the one who had taunted him that morning and paused, just for a moment, to let the recognition be shared. “Help me, please.”

The man now was desperate and Dragos yelled: “Let go of the door!”

The driver realized he was holding the door closed and moved his grip, grabbed the brake handle and wedged his foot against the handbrake and the floor.

As he gained his footing, the fireman came to eye level with the sight-glass. It was broken—exploded from the inside. Steam shot out the empty frame of the tube and he realized that the fire was undoing the steel holding back the roiling steam, now pressurized to hundreds of pounds per square inch. The crownsheet was stabilized by an array of stays, arrayed along in rows from the top of the boiler, linking the top and bottom together. If the crown were to buckle and fail, the stays would be pulled past their limit and the fasteners holding them in place would pop, leading to a catastrophic explosion.

Dragos pulled the door open and flipped it around, grabbed the driver and hoisted him free. The fireman scrambled up, fairly pulling his rescuer down into the cab as he climbed up and out. The heat bloomed in the space and the bolted end of the boiler starting to leak steam. Dragos still had his harness clipped around his waist and as the firemen scrambled out, he pulled Dragos off-balance and half-way into the cab and a loop of his harness caught on a hissing valve. Dragos tried to pull himself out, but the valve was over his head and he could not reach it as he desperately tried to twist free. In his writhing to wrench himself away, his head struck the edge of the door and he was temporarily dazed.

Maurice jumped up on the ledge of the cab, slipping on the oily surface. He grabbed the edge of the opening of the cab and leaned inside. The valve that had hooked Dragos had started to turn and steam leaked furiously from the sealing nut. Maurice grabbed the rope, the skin on his hands burning and turning instantly to scarlet, but still he managed to pull Dragos free. With his uninjured hand, Maurice pulled his friend out and lowered him to the ground, who rolled against the truck of the train.

As Maurice leaned half-inside the cab and looked to see if there was anyone left in the smoky fogged murk, the crown, at the highest point tortured the longest by the intense heat, ballooned into the firebox, a bubble of steel. The retaining stays lengthened and as the crown stretched the rivets pulled through the holes in the sheet, now as soft as cheese. The thickness of the steel thinned to a mere eighth-of-an-inch. With a roar, bubble burst and the boiler erupted. Superheated water dumped into the fire and steam at 200 thunderous pounds-per-square-inch blew into the firebox, blowing away the door. A shock of steam and smoke shook the cabin and split the roof of the locomotive. Shrapnel showered the woods and the men running for their lives.

Maurice was vividly aware of what would happen next. As the blast hit, he covered his face and braced. But the explosion was powerful and he was slammed against the back of the cab, his head jerked and smashed against a handrail. He felt nothing more. The heat and fire and smoke sizzled and hungrily devoured his clothing, skin and sinew.

He crumpled onto the floor of the cab, consumed.

-Excerpted from The Bearers by Michael Violette

Originally Published in InCompliane Magazine April 1, 2014