By Mike Violette

Article first appeared in EMC Magazine, Volume 4, Quarter 2. 2015

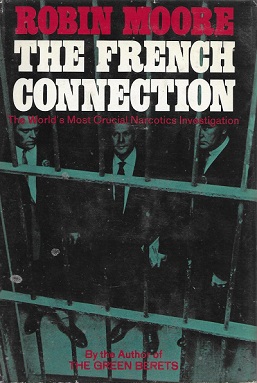

I grabbed an old copy of The French Connection from my mother’s bookshelf. The paperback, doggy and yellowed, is a chronicle of “The World’s Most Crucial Narcotics Investigation.” It is also a peek back to a certain period narrative style (Joe Friday of Dragnet keeps ringing in my head), the art of surveillance in the day and the coordination of a highly choreographed stakeout at a large heroin bust that went down in New York City in the winter of 1962. The book includes detailed descriptions of undercover wiretapping methods and modes of police radio communications in the 1960s.

The “War on Drugs” really began post-prohibition when the Mafia started exploring illicit and profitable money-making opportunities after the running of rum was no longer lucrative. After WWII narcotic use shot up, particularly in New York and heroin became the new cash cow. Smack was produced from poppies grown in Turkey, processed into a sticky paste in Lebanon and refined in the South of France, hence the “French Connection.”

The heroes of the tale, Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso, are young undercover narcotics detectives working a Manhattan beat. Eddie is described as a “burly Irish-handsome redhead” and nicknamed “Popeye” because he loved “popeyeing around,” admiring the dames. Sonny is contrasted with his ebullient partner, a skulking “worrier.” Although tall and wiry, he “had earned a black belt in karate, and, as a number of hoodlums had discovered,” could kick butt.

The narrative opens with the pair having a few drinks at the Copacabana night club, “The Copa” (rye and ginger for Eddie and sweet vermouth, rocks, for Sonny). They notice a group of 12 having a great time, who “might have been transplanted from the set of a thirties’ gangster movie: swarthy, sleek, dark-suited men accompanied by overly made-up women.” The center of attention, prime suspect Pasquale (“Patsy”) is described as an archetypical “rackets’ boss.”

Sonny notes that the boss-man “spreads bread like there’s no tomorrow.”

Suspicion is raised and the detectives decide to give the guy the tail, hopping into Eddie’s 1961 maroon Corvair in pursuit of a late- model blue Oldsmobile compact. At one point during the chase Eddie, wearing a “porkpie hat low on his forehead,” notes that some suspects might know they’re being tailed: “Guys like these bums, they’re so used to looking over their shoulders that they’d duck behind a tree if they were alone on a desert island.”

Cars figure highly in the story as the drug-runners—pursued surrepetitiously by the white hats—cruise all over Manhattan. The author is fond of describing them: the “battered white 1947 Dodge,” “second-hand 1960 Buick Invicta,” the cheap “Renault Dauphane,” an “old dusty Chevrolet station wagon.” The Canadian-tagged Buick turns out to be the main heroin vector as, apparently, there are many places in the body where 120 pounds of dope could be stashed, street value $32 million.

In the early 1960s, long before the FISA court and the NSA data vacuum started sucking, monitoring phone calls was not such an easy thing. Substantiation for getting a warrant to tap a line was tricky and federal law prohibited tapping phones; however, New York State had no such prohibition. The other trick was to get physical access to the TIP_RING pair that fed the phone from the street without arousing suspicion to install automatic tape recording equipment. “This sometimes required stringing telephone lines surreptitiously for many city blocks, over roof-tops and back alleys.”

Now it’s all done with the click of a mouse.

The detectives tapped several lines at Patsy’s house and luncheonette business and the tapes started rolling on a pair of pay phones in the luncheonette at Patsy’s house on 67th Street. The equipment would sense when the phone went off-hook and could record the pulse-dialing by punching holes in the tape when the call was initiated, one hole per pulse.

The author Robin Moore, in this self-described “#1 thriller of them all” pored over more than five thousand feet of recording of wiretaps and radio communications to chronicle the pursuit. The book captures the actions and motivations of various characters on both sides of the chase as well as some descriptions of tracking, tailing and monitoring suspects in the pre-GPS, pre-mobile communications world.

Radios were FM-modulated and the telephones ate nickels. “He was on the phone for about ten minutes; Sonny saw him deposit at least one additional coin.”

Although the radio system had no means of encrypting voice, the radio frequencies were a closely guarded secret. One mob boss did manage to get a hold of a transceiver, but apparently, he didn’t have the technical know-how on his ‘staff’ to change the channels when the cops switched channels.

At the climax of the stakeout and bust, three hundred police were deployed in cars and on-foot, coordinating by radio and payphones as they chased Patsy and three French suspects, “Frog One,” “Frog Two” and “Frog Three” trying to nail down the moment when the transaction was made and bust could occur. Updates were coordinated through a central command.

Even with the blanket of coverage, sometimes the prey slipped away and at one point Eddie wonders, “How could so many supposedly professional police officers blow one old bastard who stands out like a giraffe in a field of cows?”

Ultimately, after a convoluted cat and mouse game, the detectives nab Patsy and find the heroin in the ceiling of Patsy’s father’s house, who protests when confronted “Why you maka this business? I gotta nut-ting here!”

The dope is discovered hidden under a coat of fresh, still wet plaster. It tests out to be “the purest stuff anybody’s ever seen around here.” The haul included 11 kilos of heroin and “enough guns and ammunition to wipe out another ‘family’.” Ultimately, the bust would be the undoing of a major Mafia narcotics operation.

After the trial, Eddie and Sonny “walked out of the courtroom and into the sunshine.”

“What do you we do now?” Sonny asked.

“Maybe we ought to celebrate, go popeyeing around somewhere. What say we go over to the Copa tonight? There’s a new hat-check gal there.”

Sonny replies: “The Copa? Are you kidding?”

The story was adapted for film in 1971 and was the first R-rated movie to win the Oscar for Best Picture. It also won a bevy of other awards for Best Actor Gene Hackman, Best Director William Fried- kin, as well as Best Film Editing and Best Adapted Screenplay.

The French Connection © 1969 R. & J. Moore Inc.